November 12, 2023 presentation

WE REMEMBER

At Trinity St. Andrew’s United Church, we were fortunate to restore our HONOUR ROLLS — they hang on our sanctuary wall — to my right. Our master craftsman, Peter Raaphorst, built both large plaques from wood of a white oak tree he got from a farmer friend.

At recent Remembrance Day tributes, we told you about more than 30 of these men and women on these rolls. We brought their stories to life.

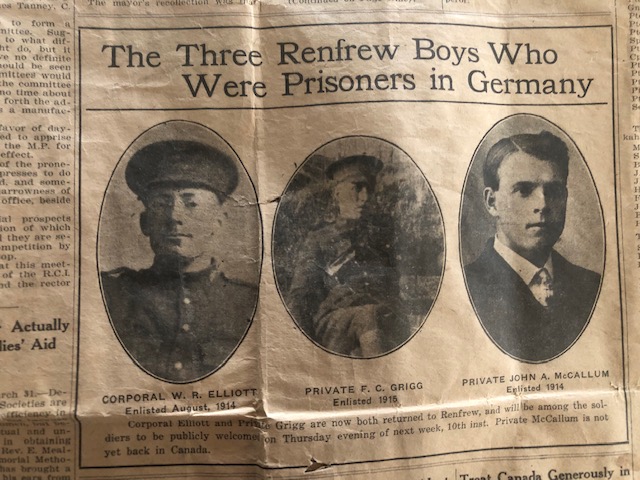

Today, we will tell you about three Renfrew men from the First World War plaques — who had the misfortune of being captured by the enemy. They spent most of the 1914-1919 war in German prison camps. But they eventually came home to Renfrew.

Frank Grigg, William Elliott and John McCallum

Corporal Elliott and Private McCallum became PoWs in April 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres. A staggering number of 6,500 Canadians were killed, wounded or captured in the first four days of this major battle.

Corporal Elliott and Private McCallum became PoWs in April 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres. A staggering number of 6,500 Canadians were killed, wounded or captured in the first four days of this major battle.

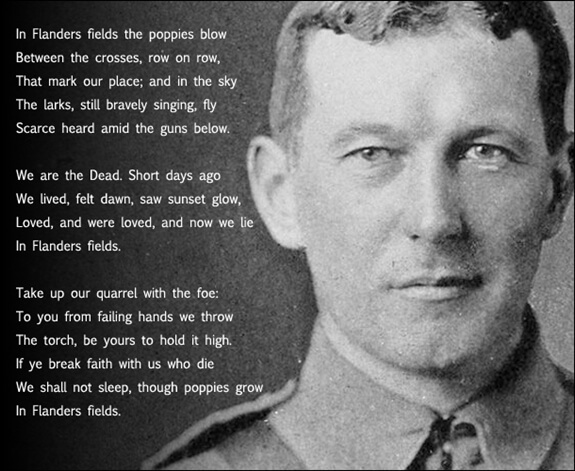

This was in Flanders Fields. After seeing the horrors of hundreds of deaths and losing his own friend on the battlefield, surgeon John McCrae was inspired to write his famous poem that has come to symbolize commemoration and remembrance.

In another Belgium conflict in June of 1916, Private Griggs was swooped up in the massive enemy attack on Mount Sorrel — 536 Canadians were taken in a single day. More than 8,000 Canadian men were killed, wounded or reported missing as a result of the fighting in overrun trenches and the artillery bombardments.

These Renfrew lads had the terrifying experience of surrendering – dropping their weapons and raising their arms. They were at the mercy of hostile German soldiers. It was an extremely dangerous situation.

They were marched far behind enemy lines to internment camps, housed in overcrowded barracks, with inadequate food and unsanitary conditions.

About 3,800 Canadians became PoWs during the four-year-long war.

By war’s end, Germany had captured 2.4 million soldiers from a dozen Allied nations. Expecting a short war, Germany was unprepared for so many PoWs. They had to build 300 prison camps — most constructed with the forced labour of prisoners of war.

As the war dragged on, it became harder for Germany to feed and care for so many PoWs. It’s not surprising that 300 of the Canadians in those camps did not survive.

In June 1916, Private Frank Grigg was interned at the Wahn prison, near Cologne/ 350 kilometres deep into Germany. It was the first of four camps he’d go to during two and a half years of captivity. He had a gunshot wound to his right shoulder.

In June 1916, Private Frank Grigg was interned at the Wahn prison, near Cologne/ 350 kilometres deep into Germany. It was the first of four camps he’d go to during two and a half years of captivity. He had a gunshot wound to his right shoulder.

Charles Franklin Grigg who was raised in Renfrew had worked out west as a locomotive fireman for the CNR. He enlisted in January of 1915 – at the age of 25. He arrived at the battlefront in France in September. He had less than a year combat experience when captured later at Mount Sorrel.

Repatriated in 1919, he came home and three months later — married Margaret (Mae) McNicholl of Renfrew. The couple had two daughters. He died in 1963 — age 73 — in a Kingston Hospital. He’s buried with his wife at the Thompsonville Cemetery in Renfrew.

Will Elliottt, a 21-year-old dry goods salesman, had enlisted with his friend, Jack McCallum, on the same day, September 22, 1914. Both men were captured in the same Begium area in April 1915. They endured three years in captivity.

Will Elliottt, a 21-year-old dry goods salesman, had enlisted with his friend, Jack McCallum, on the same day, September 22, 1914. Both men were captured in the same Begium area in April 1915. They endured three years in captivity.

In an Ottawa Citizen article, it was reported — Corporal Elliott was captured at a farmhouse near St. Julien where “the Renfrew boys distinguished themselves as real heroes and where many of them met death.”

Elliott had the “singular distinction of capturing a German colonel, single-handed, a great burly fellow, the paper said… but just as he had secured that prize prisoner, he himself was captured by a squad of Huns…”

He was taken 501 kilometres away from the front and interned in Giessen camp near Frankfurt. I imagine the march was difficult as he had suffered a bullet wound to his right thigh.

Giessen was a well-ordered camp. But for the inmates it still was “a hell on Earth.” Corporal Elliottt spent more than three years there. He got some relief in early 1918 when, being a corporal, he was part of a prisoner exchange with the Germans. He was transferred in March to neutral Holland until he was repatriated in November to England.

Back in Canada, he stayed in the Canadian army — in 1919 he was promoted to sergeant. From 1939-1954, he was a captain with the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regiment.

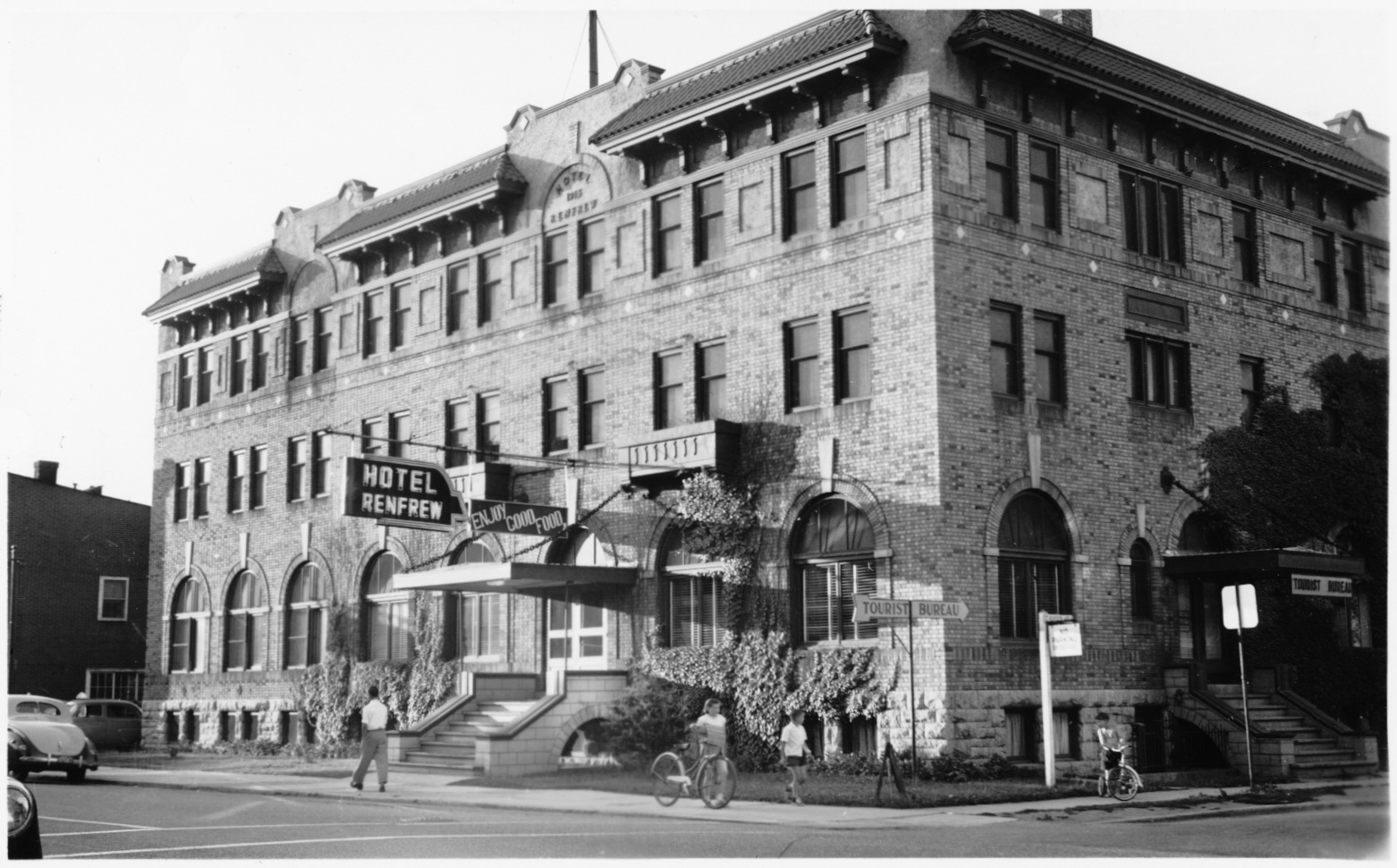

But most notably — in 1929, — Will Elliottt was a founding member of the original Renfrew executive of the Canadian Legion of the British Empire Services League This was the beginning of Branch 148. About 100 vets met at a banquet in the Hotel Renfrew which became the early Legion meeting place. Today it is the Scotiabank location.

William Robert Elliottt, a single man, died at age 71 in 1964 and is buried in Thomsonville Cemetery.

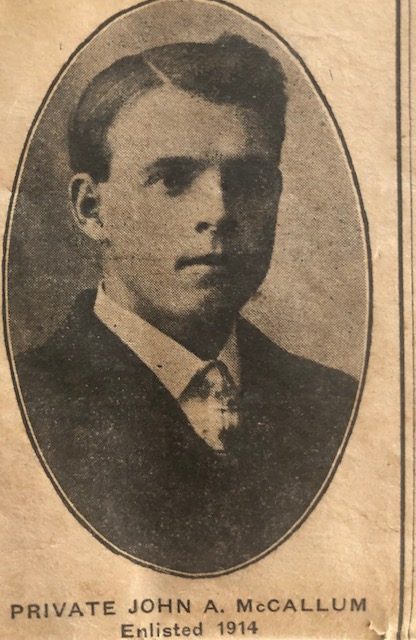

Jack McCallum, 26, a barber, was fighting with Corporal Elliottt at that famous farmhouse near St. Julian, Belgium in April 1915. In

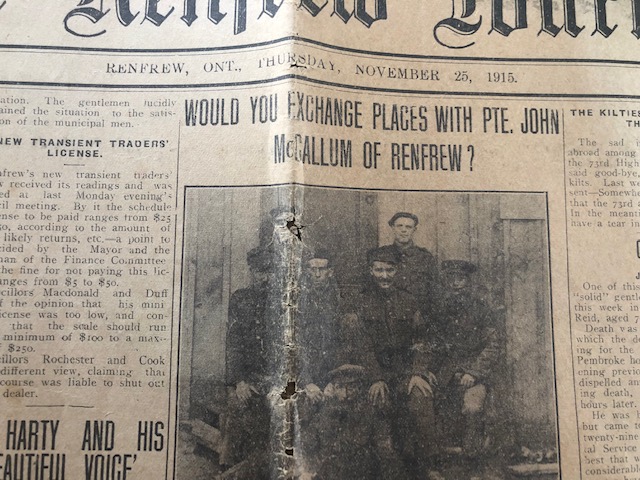

Jack McCallum, 26, a barber, was fighting with Corporal Elliottt at that famous farmhouse near St. Julian, Belgium in April 1915. In  another Ottawa Citizen article it was reported Private McCallum, with other comrades, fought until he ran out of ammunition and then used his rifle as a club but he was finally overwhelmed” by attacking German troops.

another Ottawa Citizen article it was reported Private McCallum, with other comrades, fought until he ran out of ammunition and then used his rifle as a club but he was finally overwhelmed” by attacking German troops.

The newspaper concluded that “he — like all the other boys participating in the farmhouse engagement — is the idol of all Renfrewites.”

Jack McCallum would spend three years and eight months — the rest of the whole war – in four different German prison camps – his last camp in Hameln was the largest with 30,000 prisoners. He was also forced to work in salt mines.

He had suffered a gunshot wound to the right upper arm. A few months after he was captured, Jack spent two weeks in a German hospital recovering from fever and diarrhea.

Family stories tell us that he made three unsuccessful escape attempts from camps. During one, he was beaten with a rifle butt and struck in the head. So family believed this was why Jack could fall asleep in the middle of a sentence but resume the conversation later. They called it “sleeping sickness.”

Jack wrote dozens and dozens of letters to family mostly to his mother Agnes McCallum. These hand-written notes were saved for more than 110 years. I want to thank Kathleen Hinchley, a member of our congregation, for letting me read the collection.

Shortly after his capture, he wrote to his Mother “Hope you are not upset about me being missing. Bill Elliottt & I are together. We were both wounded but getting along very good.”

And in a later letter he says “You don’t need to worry about me for we are kept good.”

As the years dragged on, Jack wrote “You have no idea how much a letter is appreciated out here.”

The Canadian Red Cross managed to arrange parcel mailings to these camps. The soldiers got tobacco products, items of clothing like warm socks, some food, or fruit in cans.

Jack asked his mother to pass on his “kindest thanks” to all his Renfrew and Burnstown friends who had sent him letters or parcels. And of course, he wanted news about so many of the young lads who had signed up for the war like him.

His ordeal finally over and early in 1919, Private Jack McCallum was back in England and wrote home: “ Well Mother, I eat about 10 times a day & then I ain’t full — so that old fatted calf is going to get some jolt when I get back.”

And he also wrote to re-assure his mother that – “I haven’t lost my head like some of the boys — taking (British) wifes [sic] back home. The girls in & around Renfrew is good enough for me”

And sure enough — finally getting home — wedding bells rang out in June of 1919 when he married Stella Livingston of nearby Grattan Moving to Toronto, they raised a family of four.

When the Second World War broke out, Jack re-enlisted again in the 48th Highanders. But this time he served as the company barber cutting the hair of new recruits at Camp Borden – and among them was his own son, John Mills McCallum who served in Northern Europe as a sniper. And he returned home to his family.

John Alfred McCallum died on October 20, 1957 at the age of 69 years old.

After this service, we invite you to look at the old photos on the TV on the wall of the narthex. And some copies of our presentation are on the table.

We Thank You.